Floyd Collins traipsed over damp leaves and thawing snow and stepped into the shadow of a cave. It was an unusually warm Kentucky winter morning—January 30, 1925—and a thick curtain of icicles hung from the lip of the cavern like the pipes of a church organ. The cave's mouth, a bow-shaped rock overhang that resembled a band shell, dripped with water.

Collins paid it no attention. This was a normal day at the office.

For weeks, the 37-year-old cave explorer had spent up to 12 hours every day clearing gravel, sandstone, and limestone from the narrow passageway winding below his feet, and today was no different. Collins removed his coat and hung it over a nearby boulder. He fiddled with his kerosene lamp and slung a rope over his shoulder. Then he dropped into a manhole-sized cavity in the ground.

When Floyd Collins emerged, he'd be one of the most famous people in the world.

HOUR ZERO

Collins dropped to his hands and knees and charged through muddy pools of snowmelt that numbed his fingers and soaked his trousers; behind him, the last beams of sunlight gasped. At five yards deep, he encountered a 4-foot drop and gently lowered himself down. He extended his kerosene lamp. The walls quivered orange.

Ahead, the cave clamped into a narrow shaft of jagged, loose rocks; Collins dropped to his belly and army-crawled under them. At 50 feet, he encountered the cave’s first squeeze, but Collins was unfazed: With proper technique, a man his size could squirm through a crack with less than 8 inches of clearance. He pressed his arms against his sides, exhaled deeply to flatten his chest cavity, rocked his hips and abdominals, and propelled his body forward with his toes.

Floyd Collins navigates a tight spot in Crystal Cave. / From the Gordon Smith collection at the National Cave Museum; Diamond Caverns, Park City, Kentucky. Photo courtesy Bob Thompson.

On the other side, the cave widened. Collins crawled like a toddler until the earth pinched closed again. He wiggled through more body-hugging squeezes and emerged at a sloping pit barely wide enough to accommodate his body.

The pit dropped 10 feet and curled horizontally into a small cubby hole that terminated at a tight crack. His brother Homer would later it as “a chimney no bigger around than your own body, lined with projecting rocks that dig into your flesh and tear your clothing." Collins had spent the previous days removing rocks from here, and the crack at the bottom finally looked passable. He eased down feet first and carefully rung his body through the enclosure. Rocks compressed his torso. Above, loose stones dangled millimeters from his neck.

The crack dumped Collins on a ledge. He brought his kerosene lamp forward and revealed a large room that dropped approximately 60 feet. Hungry to explore, he lassoed a rope around a boulder and repelled into the depths.

Then his lantern began to die. The explorer decided to turn back.

Collins pulled himself back to the ledge and carefully inched toward the horizontal crack. He laid down, flipped on his back, and pushed the lantern in front of him. He squeezed his arms against his sides, exhaled, and snaked forward into the squeeze.

Suddenly, the cave plunged to black.

Collins had knocked his lantern over, and the darkness was unfathomable. (Sight is so meaningless in these conditions that the fish living in the underground rivers of Kentucky’s caves have ) Collins, however, did not panic. He’d been caught in the dark before. He wormed toward the bottom of the 10-foot pit and dug his foot against what he thought was the cave wall.

He lunged forward. Behind him, a rock crumbled. His left ankle suddenly throbbed.

Collins instinctively paddled his feet, bucking the fallen rock with his right foot. Torrents of gravel tumbled around his legs and waist. The guilty stone wedged itself deeper into a crevice near his foot.

Collins heaved forward. He heaved backward. He did not move.

The explorer tried to breathe. He was effectively blind. His head sat directly below the 10-foot pit, and the cave hugged the rest of his body like a straitjacket. His left arm was pinned under his torso, his right by the rock ceiling above. He could not reach behind or ahead, nor could he roll over. Whenever he struggled, rocks tumbled into the abyss behind him or piled onto his feet. Under him, razor-like shards dug into his skin.

With his body wrapped in this stony cocoon, Collins clawed at the cave walls. Blood seeped from his fingernails. He began to sweat—and then shiver—until exhaustion swept him to sleep. He began a tormenting routine: sleep, wake, scream; sleep, wake, scream; sleep, wake, scream. Minutes melted into hours. His voice disappeared. His arms tingled numb. Pain radiated up his ankle.

For the next 25 hours, Floyd Collins received only one visitor from the world above: trickling beads of snowmelt that slowly, methodically, dripped onto his face drop, by drop, by drop.

Floyd Collins might have been a farmer, but he knew from an early age that the riches of Kentucky’s land lay not in the soil but in the tunnels below it. His family’s log cabin sat four miles from Mammoth Cave, an international tourist attraction that contained a palatial system of caverns bigger than most mansions. Dozens of smaller private caves dotted the landscape. Growing up, Collins dreamed of discovering his own.

Collins began exploring Kentucky’s caves alone when he was 6. As a kid, he’d ride to the Mammoth Cave Hotel with his father, Lee, and sell tourists rocks and arrowheads he had found underground. By 10, he had dropped out of school and was scouring local caverns with a lard-fueled lantern in pursuit of Native American relics. By 12, he had memorized the turns of the nearby Great Salt Cave and was venturing off established paths, discovering moccasins, tomahawks, beads, footprints—and even the occasional body of explorers who came before him.

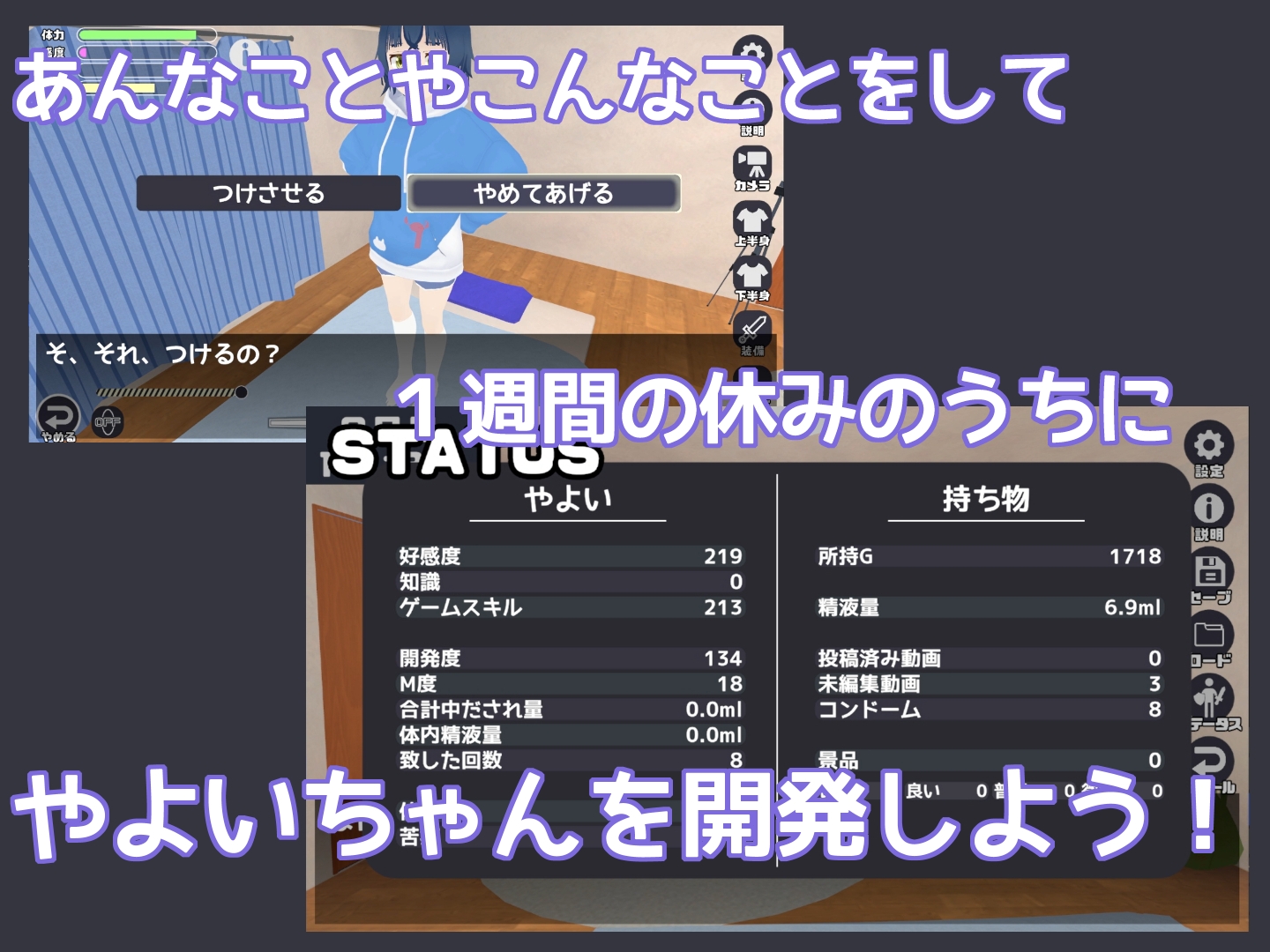

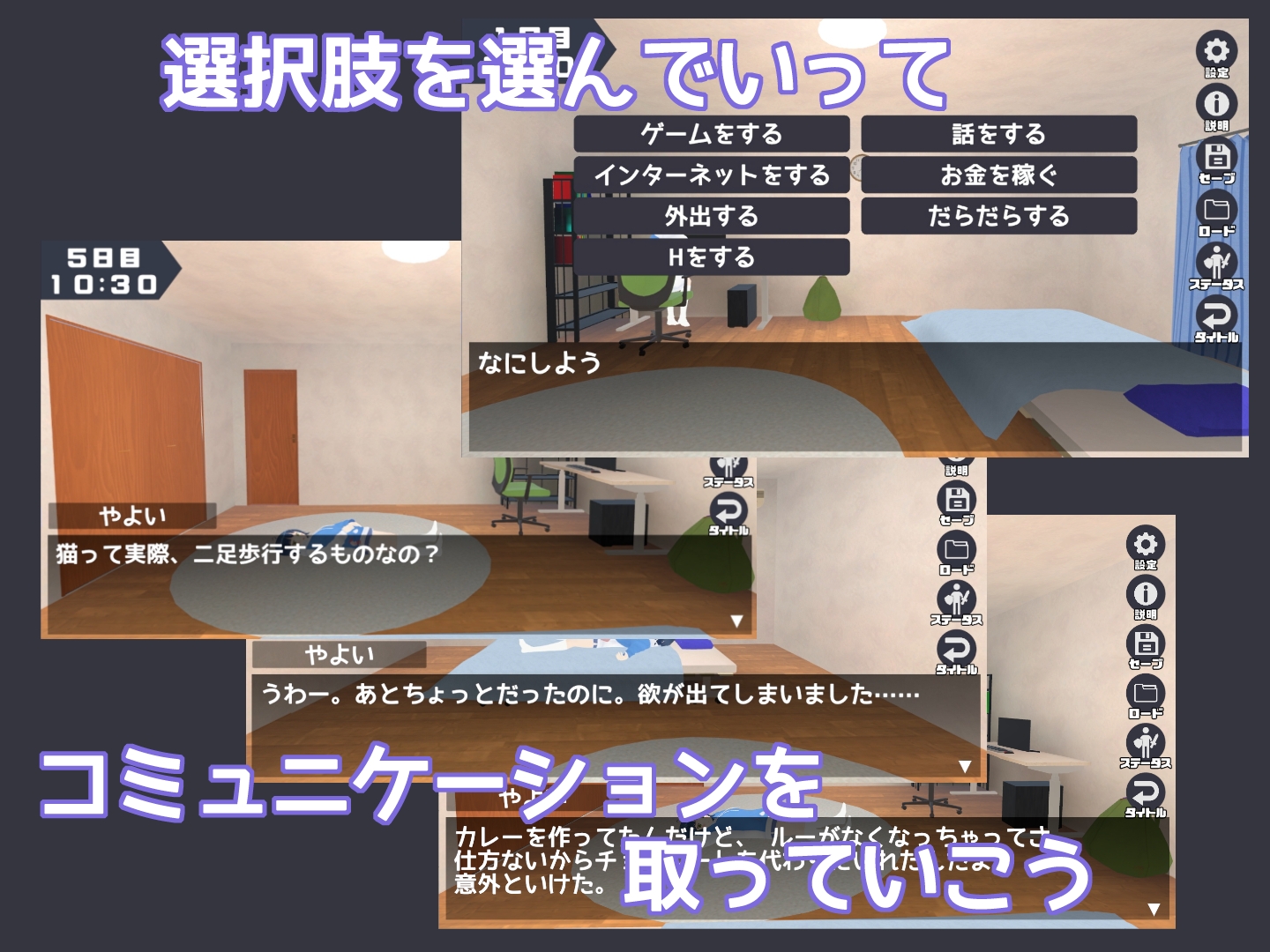

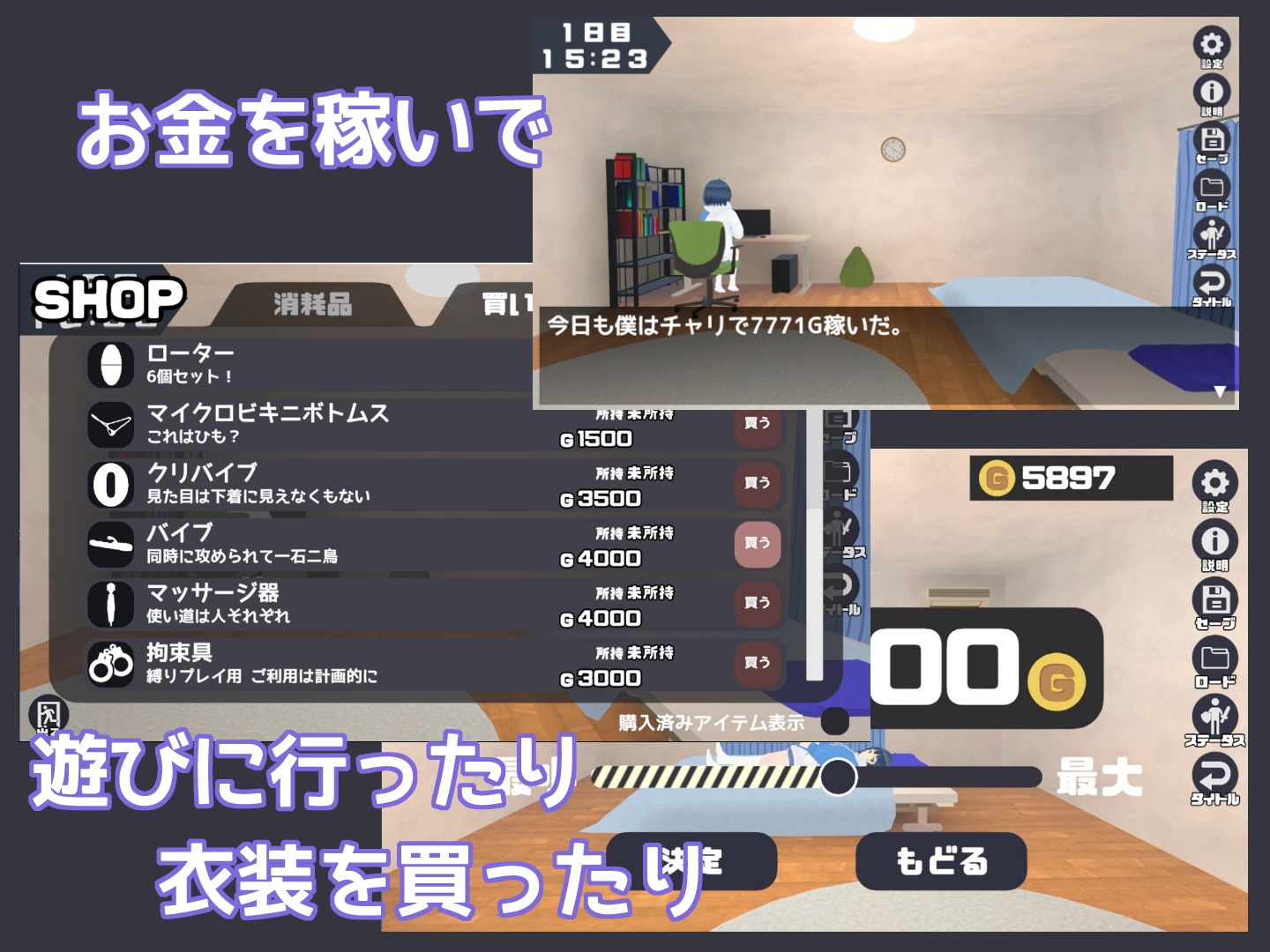

やよいちゃんを開発したい!

やよいちゃんを開発したい!

ถ้าชอบก็ช่วยกันโหวตหรือตอบกลับกระทู้ให้หน่อยจ้า

ถ้าชอบก็ช่วยกันโหวตหรือตอบกลับกระทู้ให้หน่อยจ้า